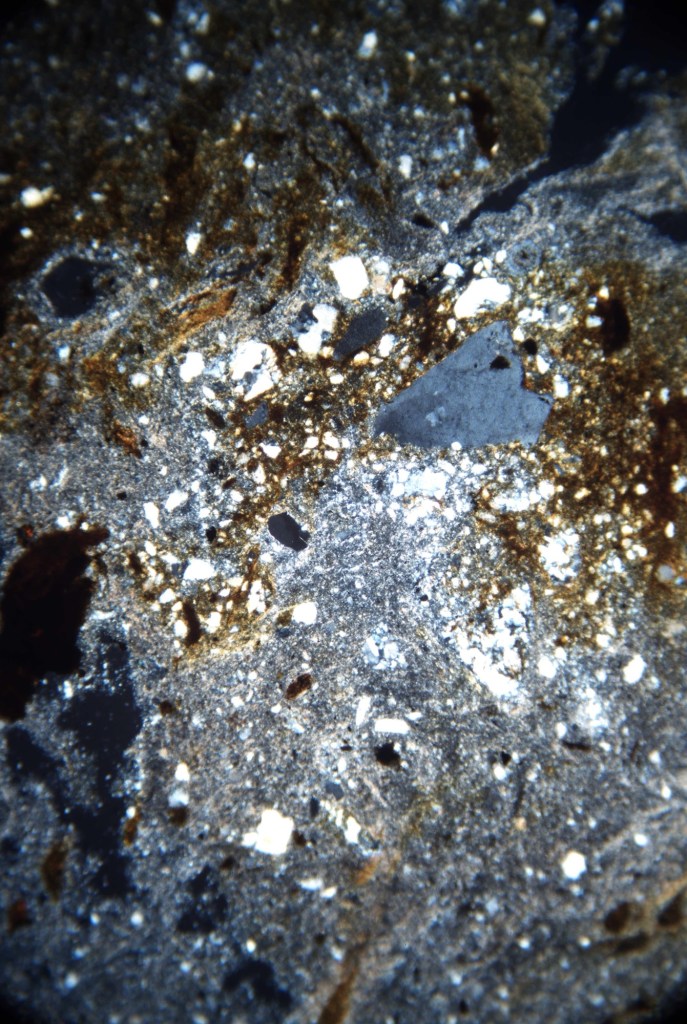

In 1984, I worked at The Museum of London as a volunteer, helping with post-excavation work and the back-catalogue of ceramic artefacts held in the museum stores under the careful supervision of Dr Paul Tyers. Part of the work involved preparing samples of Roman pottery for thin-section analysis, which involved cutting a small slice of ceramic from a shard, mounting it on a glass slide and then rubbing the ceramic down until it was the required thickness (a few microns as I remember). After this process, you could view the ceramic sample under a microscope, carefully illuminated with cross-polarised light for example, and the specific characteristics of the material would be presented to you: particles of quartz and other minerals, air spaces, the orientation of particles after being worked in a particular way…. This petrographic analysis has enabled archaeologists to determine the location of clay sources and the ceramics produced from them, thereby helping map out trade routes and connections between localities, regions, countries and continents….

With the iron-rich Devon clays project (2023-24), there was a focus on examining the specific qualities of the materials I was lucky enough to collect, along with rekindling links to fellow archaeologists who I studied and worked with in the 1980s and who now live in this beautiful, diverse county. Revisiting thin-section analysis became a growing priority for this project, but re-engaging with this process was only made possible with the help of Dr Charles French and Tonko Rajkovaca at the McBurney Laboratory (University of Cambridge). Huge thanks to both of them.